Anna Hunter fell in love with knitting as a teenager, as both a hobby and a way to keep her hands busy. Years later, in 2009, on a break from stressful work as a frontline anti-poverty advocate in Vancouver, she opened a wool shop called Baaad Anna’s (get it?) with the intention of featuring 100-mile yarn — only to discover that despite all the region’s sheep farms, locally produced wool was impossible to find.

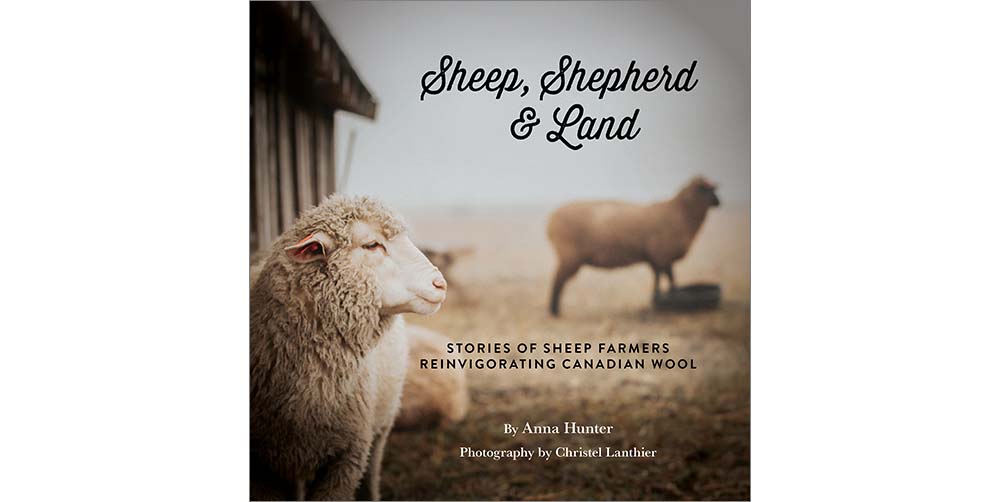

After a number of years running the shop, Hunter and her husband decided to move their family to a more rural environment and ended up on a 140-acre property in eastern Manitoba, now known as Long Way Homestead. While their original intention was simply to farm for themselves, there was so much interest in their journey that she started sharing her story with others — which led to keeping sheep, then processing and selling wool. Her latest venture? Writing and publishing the book Sheep, Shepherd & Land: Stories of Sheep Farmers Reinvigorating Canadian Wool. (It has a companion book of knitting patterns, too.)

Hunter’s book and business are a reminder to small makers and business owners that we all have the power to make a difference in how our industries operate, such as by purchasing materials that are environmentally responsible and aligned with our business values. (One relevant example? Workshop member Susan Pfeiffer switched from polyfill to wool stuffing not long ago for her product line.)

Here, we speak with Hunter about the book, her journey and her dreams for the Canadian wool industry.

Workshop: How did you get from downtown Vancouver to processing wool in rural Manitoba?

Anna Hunter: I didn't think I would start a business again. But because of Baaad Anna’s and my connection there, there were all these knitters who were intrigued by the idea of raising sheep. I started sharing my story, and quickly tuned in to the disconnect between knitters who are excited [about local wool] and sheep farmers who can't get their wool processed and into the hands of knitters.

I decided to start a sheep farm and went full-in raising sheep. Within a year I realized, the big problem is infrastructure. We can't get that wool from sheep into a format that knitters want. So in 2018, we opened up a mill. We're the only mill in Manitoba. We're still on that journey of sheep farming and running a mill and trying to create connections between producers of wool and consumers of wool.

W: What products do you sell from your farm?

AH: We focus on yarn and fibre. We sell wool pillows and duvets. Wool is hygroscopic and temperature regulating, it filters bacteria and dust mites and it's easy to clean. It makes excellent bedding.

We also do wool pellets, which is a new, interesting [way to utilize what would otherwise be] waste wool. There's always wool that's so dirty, you can't turn it into any sort of textile. We pelletize it and it becomes a garden amendment, like a fertilizer. That's an exciting opportunity that gets our own mill closer to zero waste, but can also be a response to where the industry is at right now, where most wool is underutilized. But we can turn it into pellets and start putting those nutrients back into our soils.

W: The wool market is pretty big in Canada, right?

AH: It's grown exponentially. Anecdotally, I started Baaad Anna’s in 2009 and it was bananas how quickly that industry grew in Vancouver. COVID hurtled it forward again, where people were stuck at home and picked up things like knitting and different fibre arts.

W: Let's say I wanted to find some nice Canadian wool to make a line of hats with. How hard is that right now?

AH: It’s not easy. If you're willing to do the work, you can do it. But it's not as easy as walking into a local yarn store. I'd say most local brick-and-mortar yarn stores across Canada have less than two percent of their shelves filled with Canadian-grown and -milled yarn. And most have access to our two big mills: Custom Woolen Mills in Alberta and Briggs & Little in New Brunswick. The rest are small mills like myself that have pretty small output.

What I've noticed now is people find their favourite sheep farmers. They find those little mills that they love, and then they are loyal customers. But it takes some work. And that's part of what I would like to see change: making Canadian wool more accessible and just as easy to find as commercial wool.

W: That brings us to the book. Where did the idea come from, and how did that unfold?

AH: When I was first a knitter, and even when I opened up Baaad Anna’s, I probably could have named three sheep breeds: Merino, which we all think is synonymous with wool; BFL [Bluefaced Leicester]; and maybe Shetland. I had no idea there were so many domestic sheep breeds out there, and how much variety there was within those breeds.

Once I started looking for sheep to raise myself, I became exposed to all these different sheep breeds. It was a huge eye opener. I dove right in — I consumed every little bit of information I could about sheep breeds. It changed the way I perceive wool and knitting and fibre arts, and I wanted other people to know about it. So I started teaching. I was teaching for years, and then the pandemic shifted the way that happened and I thought, I need a better way to spread this information. That's where the book started. I want other knitters and fibre artists across the country to understand all the amazing sheep breeds that are out there, how they're connected to different land bases, and how that can inform their practice.

W: How can Canadian makers find sources of wool in their regions?

AH: Wool is not seen as an agricultural commodity. There's no one studying it in Canada in a meaningful way. So I started a research project to look at what fibre farmers across the country were doing, where they were selling, what their barriers were. And the results of that were really interesting.

The number-one challenge for farmers who are focusing on wool production is marketing. They have a hard time reaching customers. They're already farming, shearing, sorting, caring for animals, all these things. They don't have time to attend fibre festivals, partner up with designers or figure out labelling.

The result was a website I started as a side project. It's canadianwool.org and among other things, it has a province-by-province breakdown of sheep farmers and what they sell. The thing I love about it is that it's decentralized. There's no gatekeeper — any farmer can put their information up there and any consumer can go and look at who's around and how to contact them.

That’s the first way: check out that website and get connected to your fibre farmers. If there's a fibre festival or show in your region, there are often farmers that'll show up. And another one I'm a fan of is talking to your local yarn stores and asking them to prioritize bringing in local yarn. It's tough — yarn stores have to make their own profit margins. But I think if we can make it more commonplace, we can reduce some of those barriers and help it make [financial] sense for both yarn stores and farmers.

W: You’ve said that the industry is in crisis. Do you think that there are positive signs now? Where would you like to see things in five or 10 years?

AH: I am extremely hopeful — maybe naively so. There are more entrepreneurs and folks like Wave [Weir] and myself who are opening mills, doing things differently and connecting, and I think that's really exciting. Campaign for Wool Canada is taking a more high-end approach that will help the overall promotion of wool at a national level.

If I look forward to where I want to be, or where I want the industry to go, I think a necessary step is leadership that can unite sheep farmers across the country. If we could have some unification around how much wool is worth and what happens to it, we would see a real shift in the industry.

But then to bring it back to a fibreshed focus, I think the best way that we can do that is by regionalizing our production. What we have in Manitoba and Saskatchewan is different than Atlantic Canada in terms of quantity of wool being grown and potential production. So let's come up with regional solutions that can build jobs in rural communities.

W: Why should makers buy Canadian wool?

AH: I might change the question slightly. Why should Canadian shoppers buy breed-specific wool that's raised in Canada? Because it helps preserve the genetic diversity of different sheep breeds. Why does that matter? Some of these breeds have been around for hundreds and thousands of years. But because they aren't considered commercial breeds, we risk losing that genetic diversity. To me, that is a problem no matter what. When we seek out Canadian breed-specific yarn and fibre, we help conserve those breeds and we support those small farms and mills. That's one answer.

The other one is it makes sense economically and environmentally to consume resources that are grown within our geographical regions. It's irresponsible to continue consuming massive amounts of textiles with the amount of emissions and carbon footprint and miles that exist with a lot of the products that aren't sourced and processed domestically. We've seen the fragility of our supply chains and our environment. And a lot of that has to do with the textiles we consume.

Globally, textiles are a major polluter and source of emissions, and most of the textiles in Canada — including our yarn, fibre and wool-based products — come from low-wage countries where environmental regulations are not as rigorous as here. If we are truly committed to preserving our planet and fighting climate change, we need to reduce emissions. And if we want to build economic viability and vibrance in our community, especially in rural communities where farming happens, we need to support our local Canadian wool industry.